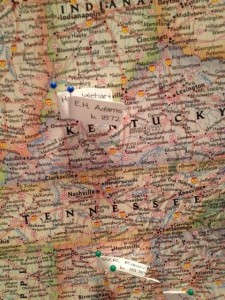

I love looking at my genealogy map, which hangs on the wall in my office. Using color-coded pins with little label flags, I pin my ancestors’ birth and death places.

I love looking at my genealogy map, which hangs on the wall in my office. Using color-coded pins with little label flags, I pin my ancestors’ birth and death places.

As much as I enjoy adding pins to the map, I probably let a year lapse between pinning sessions. But just the other day I took a little time (as part as my weekly genealogy research commitment) and added ten ancestors to the map. It was a fun exercise — and it was educational too.

Focusing on ancestors’ birth and death places helps me think about migration. Looking at the map makes that migration feel more real.

I added a generation in my latest pinning session, so I now have five generations pinned on my map. I was born in Washington state; as I go back in generations, I go farther east with the pins. (Not a big surprise, I know.)

In this past pinning session, I reached an eastern seaboard state, Georgia. A glance at the map showed me that the distance from Georgia, where my great great grandmother, Margaret Elizabeth Dye, was born, to Alabama, where she died, wasn’t as far as I’d thought. Margaret was born in 1844 in Henry County, Georgia and was married in 1865 in Shelby County, Alabama. Her husband, Laban Taylor Rasco, was born in Alabama and did fight in the Civil War in Georgia, so maybe she was a war bride? (I’m thinking not because there were many Dyes in the cemetery where she is buried in Cullman, Alabama.) These are the kinds of stories I hope to suss out as I look to go deeper, rather than higher, in my family tree.

The map helps bring questions to light, making migration patterns more visible. I know that there are higher-tech ways to do this. But my old-school map and pins make me happy.

I’m not sure how I happened across the website

I’m not sure how I happened across the website