When I rebooted my genealogy research a few years ago and started my family tree from scratch, adding only those people for whom I had verified source information, I focused on my direct-line ancestors. That approach felt less overwhelming, less tedious, and it allowed me to move up my family tree more quickly, which felt rewarding.

When I rebooted my genealogy research a few years ago and started my family tree from scratch, adding only those people for whom I had verified source information, I focused on my direct-line ancestors. That approach felt less overwhelming, less tedious, and it allowed me to move up my family tree more quickly, which felt rewarding.

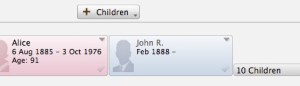

In August 2013, I pondered whether I should be adding collateral lines (the siblings of my direct ancestors) and concluded it would be a good idea. I started adding children I found on censuses, properly sourcing them, of course. It did prove to be a bit tedious and it sort of dropped off my radar.

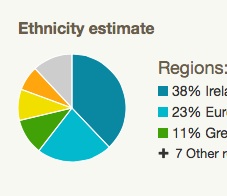

Then I took an Ancestry DNA test and transferred my DNA results to Family Tree DNA. Since then I’ve been contacted by a number of distant cousins. While I’m still trying to figure out how to use the DNA results to further my research, one thing has become very apparent: Having those siblings in my family tree would help me, as well as these cousins, figure out our relationships.

I’d like at the very least to have their name and approximate birth dates, easily obtainable from my ancestors’ census records. More information would be great, and maybe I’ll do more research on these siblings eventually, but right now I’m setting my sights on names and birth dates and states.

So I’m going for it. I’ve moved the goal of adding collateral lines to each family to the top of my list of things to accomplish when I’m focusing on a certain line. I’d added a sheet called Siblings Entered to my progress tracker. (I was glad to see that I’ve already entered the siblings of eleven ancestors; it’s a start.) The clues these collateral lines will give me should make them less tedious to enter. At last, I’m really seeing the value of the effort.

I look forward to having a more robust family tree!

This past October, I wrote a post called

This past October, I wrote a post called  Last spring I

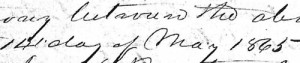

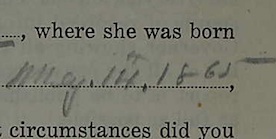

Last spring I  In researching my great great grandparents, Laban Taylor Rasco and Margaret Dye Rasco, whose graves I saw last month in Alabama, I realized that I was seeing marriage indexes that listed their marriage date as March 14, 1865, but in my Reunion software, I’d listed May 14, 1865 as the day they wed. The source for the May date was the

In researching my great great grandparents, Laban Taylor Rasco and Margaret Dye Rasco, whose graves I saw last month in Alabama, I realized that I was seeing marriage indexes that listed their marriage date as March 14, 1865, but in my Reunion software, I’d listed May 14, 1865 as the day they wed. The source for the May date was the